- Home

- Andrea Molesini

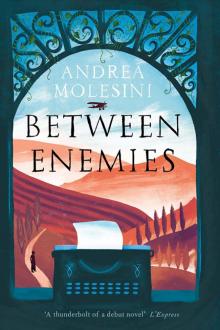

Between Enemies Page 13

Between Enemies Read online

Page 13

‘We are hiding nothing. We have no weapons,’ protested Grandpa mildly.

The sergeant stopped stroking his moustache and his glower darkened. He seized Grandpa by the lapels, and this time Grandpa paled. I had never seen him like that. He was more surprised than frightened. I took a step towards him but Teresa beat me to it. She shouldered the sergeant off and stabbed a finger straight at his nose. Staggered, he took a step backwards.

‘Cowardly scoundrel!’

‘Calm down, calm down, nothing’s the matter, Teresa. Take it easy and let them search for what they want. We have nothing to hide.’ Grandpa straightened his jacket collar. ‘There are no weapons here, Sergeant.’

The search resumed, even more wild and violent. The men now hurled the pans onto the floor with greater rage and fury than ever. It was their way of showing us who was top dog. After the kitchen came the turn of the downstairs rooms, one after another. I took Grandpa out of doors, into the garden, and we strolled around for a while.

‘Defended by a servant! If this is what this world is coming to, I don’t mind going to another,’ said Grandpa, then clammed up. After half an hour we went up to the attic. The search, with din and devastation, continued far below. Grandma and Aunt Maria had been to protest to the baron, who had stayed immured in his office and hadn’t even received them.

I followed Grandpa to the Thinking Den. We sat and smoked, he an inordinately long Tuscan cigar, I my pipe. On the desk between us towered the black bulk of Beelzebub, reducing the little Buddha to the status of a minor god. Grandpa had an urge to talk, to give an account of himself. Even he, who in one of those aphorisms good for the dinner table had said that men do not do so, and that if they do it is to conceal, not to reveal.

‘I have always been a prisoner,’ he said quietly but clearly, with a tiny pause after each word. ‘Yes, a prisoner, you heard me right.’ He was not even seeing me, but fixing his gaze straight ahead, on the smoke from his cigar. ‘I have never been able to kick the current Kraut in the teeth.’

‘What do you mean, Grandpa?’

‘A man who is really a man soon learns to fend for himself, to cast aside all safety and convenience…He has to learn it early!’ He blew a smoke-ring. ‘I’ve been scared of the truth…When you tell the truth you lose friends, you lose everything. The truth hurts, because it brings you right back down to earth. And that’s what we all try to avoid.’ He still wasn’t seeing me.

‘You mean, back to reality, not dreams.’

For an instant, a bare instant, he saw me there. ‘Defended by a cook…a servant…’ He sighed, as if to get a load off his chest. ‘That woman Teresa is worth more than me, she’s got more guts than me, she’s of more use to the world than I am.’

‘Her rabbit stew wasn’t bad…in its wartime way.’

‘You know what the trouble is, Paolo? The trouble is that we have the priests sitting on our heads. They’re the ones who school us, and they it is who have least faith of all. They believe in God’s nest egg all right, because it’s useful, but for the rest… Just draperies and incense to dress up all their natter about nothing. What do they know of the fire that burns within us? They don’t see their wives and children die. What do they know of the kingdom of the dead? They fear it and they avoid it, as do we all, but what do they know of it? They believe in the Church, yes that, because their Church has walls and money, but when they turn to their god…They’ve always burnt visionaries alive. If a peasant sees the Madonna they don’t pat him on the back, they put him on trial! But then if other people start to see Madonnas where the peasant they burnt saw his, then they say, “Yes, the Madonna appeared here,” and build a chapel, then a cathedral, a monastery. That’s how it works with them. They think they are lambs among a pack of wolves, but in fact they themselves are the wolves. There is no hellfire, but the truth is a flaming fire, and the truth is our hell. Our cook showed me today that she has more truth to her, more life in her, than I have.’ He looked at me then, and he saw me.

‘She’s a very special woman. I’m fond of her too.’

‘She is a great-hearted woman.’

‘Heart’ was a word Grandpa never ever used.

‘We Italians are the progeny of priests, we detest joy. It scares us. Foreigners say we’re a happy-go-lucky people, but they’re wrong. We clip the wings of happiness as soon as it’s heard in an infant’s cries, because they’re a disturbance. But the world needs disturbing, and how!’ He looked at me, but again without seeing me. ‘These bars that imprison me I have fashioned little by little over the years, day by day. They are forged out of my fear of disturbing the world.’ He stubbed out his cigar in the ashtray he kept beside Beelzebub. He laced his fingers at the back of his neck, leant back in the creaking chair, and raised his eyes to the ceiling. Something resembling an expression of serenity spread across his face, and a smile appeared beneath the moustache he no longer had. He was my old Grandpa again, with the face that laughed even when he was sad.

‘Grandpa, do you remember when you were teaching me geography?’

He roared with laughter. ‘You refused to learn the word “antipodes”.’ His hands described a globe above Beelzebub. ‘Italy and New Zealand,’ he said, pointing his index fingers at each other, but from a distance, to convey the notion of a map of the world. ‘New Zealand and Italy, you couldn’t grasp the idea. And then suddenly you said, “New Zealand is a boot upside down, Grandpa; it’s Italy fallen onto the other side of the ball.” It was a wonderful moment…You’d made me see something I’d had in front of my eyes all the time.’ He laughed again, and added in the grave tones of one of his grand pronouncements: ‘War also is like a child. A child who every so often shows us what we’ve had before our eyes and never seen, because we’re too careless or cowardly.’ He sighed. ‘Two things which, at bottom, are very much alike.’ He fell silent for a while to mark the change of register, then said: ‘How’s it going with Giulia?’

‘Well.’ I was expecting to blush, but I didn’t. With him I felt safe.

‘I’ll see for myself when you’ve been for a good ride on her…You must be ingenious. As I told you, that one is a mare’s crupper!’

Eighteen

I HAD WOKEN UP WITH A HEADACHE. ‘WHAT I NEED IS A good walk,’ I said to Grandpa, who without deigning to glance at me went straight to earth in his Thinking Den. I left the house without breakfasting. I wanted to be alone. It looked like rain. I went as far as the little temple and lit my pipe. I began to feel better, and after a few minutes I set off walking again, doing the round of the park. With the air making my eyes smart and firing up my mind, I thought back over what Grandpa had said. That a man had to learn to fend for himself early in life. I’m too meek, I thought.

I stopped outside the barn. I knocked at the steward’s door but got no answer. On the floor above his quarters the hayloft was divided in two by a thin partition of larch-wood planks; on the left was usually piled the fresher hay, on the right the seasoned stuff, which had all been carried off by the Germans. I climbed the wooden ladder and went and sat in the right-hand part, the empty one, as I didn’t want to get my breeches full of hay. I spread my legs and leant back against the partition. It began to rain. I loved the smells that the first rain reawakens, of wood and grass and soil and dung and leaves: everything revives. But suddenly I was startled by the voices of Loretta and Renato, talking excitedly. I thrust my pipe into my pocket, still burning but with my hand over the mouth of the bowl, and flattened myself against the partition.

Between the planks there was a gap of a finger’s breadth. She was clambering up the ladder. He was following. ‘If this is what you’re after…But you’ll take me up the bum…I’m not taking any chances, see?’ He didn’t even remove his overcoat, just unbuttoned it. With quick, precise movements worthy of a gunsmith he stripped off her cloak and blouse, revealing her enormous milk-white breasts. He bit them, eliciting a little cry which he stifled by turning her round and pressing her head down in the h

ay. She spat out bits of hay, while he spat in his hand and took her brutally. Again he stifled a cry from her, pushing her face right into the hay. I saw his heavy boots grazing her ankles, saw the skin reddening. And when she, spluttering out hay and sobs and saliva, managed to moan, it was only to mingle her pleasure with his. Then, for a long moment, I fancied I could hear the woodworms at work in the rafters amid the rain battering at the tiles.

Buttoning himself up, Renato lowered his head slightly so as not to knock it against the beams. Loretta could not find the strength to get to her feet, or to look at the man who had taken her in such a way. She kept spitting, wiping her eyes with her fingers. With trembling hands she felt for the knickers rolled down round her ankles. With a handful of hay she wiped at the blood already drying at the backs of her knees.

Renato went down the ladder first, disappearing into his quarters. From my perch I saw Loretta walking slowly, weeping and hobbling in the rain. I saw her heading for the latrine. She couldn’t go back indoors at once, because her mother would have guessed all.

Nineteen

GRANDPA AND I WERE WATCHING GRANDMA COUNT UP THE gold sovereigns. They were her little nest egg, craftily wrested from the fury of the plunderers. Grandma had sent for Renato. When he entered the room Grandpa turned his face to the wall and stared at the whitewash. Grandma handed two gold sovereigns to Renato, who was limping more heavily than usual. ‘You know how best to use them…We’ve run out of flour…and get a few pieces of dried meat too.’

Renato glanced down at the coins. ‘It’s not enough, madam. The prices are going up along with the risks. This quartermaster in Sernaglia…If they find him out they’ll shoot him.’

Grandma avoided his eye. ‘Take care not to get yourself killed, Signor Manca,’ she said quietly.

Renato looked at me. He didn’t know I had seen what had gone on in the hayloft. He gave me a long look, with hard, cold eyes.

‘Where I come from, madam, we slaughter the boar, not the pig, and falcons for us are chickens. If there’s something to be done we do it, or something to be said we say it.’ He tossed the two sovereigns in the palm of his hand until a third one stopped him.

‘That’s settled, then,’ she said.

‘I’ll be back at midday tomorrow.’ Renato took another look at the coins. ‘This is Queen Victoria,’ he murmured.

‘Old savings…but gold doesn’t age.’ Grandma dismissed the steward with a brusque gesture, which she then softened with a smile. But he had already left the room.

Grandpa protested: ‘I could have gone myself.’

‘Real life is my province.’

Grandpa went out, slamming the door. I followed him.

The rain had turned to snow, getting heavier and heavier. I took Giulia to the hayloft. There were only a few soldiers about the place, and those few preferred to stay in the warm, along with the mules, drinking the wine they had filched from the peasants. We climbed the ladder, and I stretched out on the hay and kissed her. I wanted to make a show of strength and determination, to take her at once, but she shoved me roughly away and looked at me as one does a stranger. ‘There’s someone crying… Can’t you hear?’

I hadn’t heard a thing.

Giulia stood up. She no longer had that ridiculous gasmask hanging on her belt.

But now I heard it too, a stifled wail. I got to my feet. I had hay all over me, even in my shirt collar, and it was itchy.

A sob. We both scrambled up the pile of hay on all fours. At the far end of the hayloft was a dark space littered with barrels and casks. The Hohenzollern thugs had stripped all the meat off the beast and left only the bones for those of the Hapsburgs. There was an acrid, sickening stench.

The cry was like that of a trapped cat. Giulia asked me for a match. I handed her the box. ‘Watch it! The hay!’ The match showed us the jumble of bits and pieces. A second match solved the mystery: Loretta.

She had hidden under a table, between two broken barrels. Her face was wedged between her knees. A glimpse of her calf beneath her skirt showed a long, black graze. The frock beneath her open overcoat wasn’t dirty and wasn’t torn, but no doubt about it, it betrayed her roll in the hay.

‘Was it the soldiers?’ Giulia’s face was on fire. The match went out.

‘It wasn’t anything,’ said Loretta from the darkness.

Giulia thrust the matchbox into my hand. Her lips touched my ear. ‘Hop it,’ she whispered. ‘There are things that can’t be said in front of a man.’

I re-crossed the barrier of hay. Once down the ladder I turned up my coat collar and began to run through the thickening snow.

In the kitchen was Teresa, stirring polenta.

‘Have you seen my daughter anywhere?’

I shook my head. But Teresa gave me a piercing look and wielded a dishcloth and ladle like a sword and buckler. ‘It’s that female…been spinning cobwebs in your brain, she has…and she’s too old for you anyway.’

I stammered out an objection that Giulia was only twenty-five.

‘For you she’s too old, lad, that’s all I can say.’

I left the room. I found it hard to stand up to censure from Teresa. With Grandma and Aunt Maria I could manage it, but there was something in Teresa which awed me. In my eyes she was the guardian of the truth, and against the truth there’s not much to be done. It was lucky she hadn’t pressed me about Loretta, because I wasn’t a good liar.

That evening, as happened more and more, Grandma stayed in her bedroom and Grandpa, who without his wife nearby became himself four times over, set about entertaining us.

We ate in the big dining room, beneath Great-Grandma’s portrait, because the Austrian officers had all gone off to Pieve di Soligo for a reception in honour of someone or other. Teresa was serving at table. Point-blank, Donna Maria asked her where her daughter was, and she said Loretta wasn’t feeling well and had retired to bed. ‘She has a sore backside, but tomorrow she’ll be on her feet.’ Adding in an undertone, ‘If not I’ll give her what for.’ Grandpa said that there was a strange fever going around. He’d heard as much that afternoon in the bottiglieria where he’d been to listen into the world ‘with wine before and farts behind’, and that in the hospital at Conegliano there were not only wounded soldiers but also patients with ‘they don’t quite know what, but rumours say it’s typhus.’

‘You like to scare us, don’t you?’ said my aunt.

‘A little pep in the air clears the brainpan.’

The cook, holding a dish of rissoles made of goodness knows what, failed to suppress a diambarne de l’ostia, and Donna Maria rebuked her with one of her looks.

Great-Grandma’s portrait, hung between the two windows, was gazing down at us. She had been a most beautiful girl, with great sapphire-coloured eyes beneath a broad brow, and when Grandpa noticed me staring at the picture he commented, ‘She had the bearing of a Baltic princess.’

‘Why Baltic?’ we all asked with one voice, but he didn’t answer.

After supper we gathered round the fire. Teresa brought us a hot lemon drink. For a while Grandpa didn’t even touch his cup, but then he furtively added a drop of ‘something strong’, because ‘what you need you need’. He detested that pale yellow brew, but it would have distressed him not to sip along with the company. Aunt Maria asked him about his book. He said it was coming along, that he was trying to get the plot straight, but he had not yet managed to get his central character properly in focus.

‘But in that case you haven’t even started, have you?’

‘I know lots about the lesser characters…But you see, Maria, it is as it is in the army. It’s the sergeants and the corporals who do all the work. The privates and the officers provide numerical strength and showpieces, but the real work is put in by the ones in the middle. Give me a good sergeant and I’ll set you up a good contingent.’ He lit a cigar. ‘Do you want to know what my story is about? It’s about the world that’s going all to blazes.’ And for a moment he vanished in his clo

ud of smoke.

Teresa in the meanwhile was starting on her round of the room. There were very many candles to be snuffed out.

Twenty

THE SKY WAS MURKY, AN ENCRUSTED STEWPOT. DRAWN UP in double file in front of the church was the Hungarian contingent in full strength. It filled nearly the whole of the unpaved road down as far as the Villa gates. We were there too, all of us, not in answer to an invitation but because Grandma and Aunt Maria said we were duty bound to do so. There were no rowdy children, no barking dogs. The alleyways were hushed. Half a dozen pious old biddies, swathed in vast black shawls, were telling their beads at the foot of the church steps. Don Lorenzo had been locked up in the sacristy with half a keg of cordial, guarded by two sentries.

Von Feilitzsch was wearing, hanging from a raspberry-coloured sash, a purple cross with the monogram of the late emperor – F J – glittering on a gold chain, supported by the beaks of the two-headed eagle. Their claws gripped a scroll bearing the words ‘Viribus unitis’. They too like to call themselves heirs of Rome, I thought.

The bell weighed a hundred kilos, and it was lowered with all the necessary caution. The ropes were handled by twelve infantrymen. It hit the ground with a dull thud. A short silence ensued. The major crossed himself, and the sign of the cross swept along the line of troops like a flutter of wings. We too crossed ourselves. Aunt Maria’s eyes, as she stood erect beneath the arch of the church door, flashed with anger.

The ceremony was over in a few minutes. The noise of the breaking of ranks merged with that of the approaching cart, drawn by two oxen with sawn-off horns. The bell was destined for some depot or other, thereafter to be melted down, or simply forgotten. Its voice would become a memory only.

‘With the same sacred symbols, the same God,’ said Grandma, walking arm-in-arm with Grandpa Gugliemo, ‘we ought not to be making war on each other.’

‘They lowered their eyes, did you notice? They were ashamed of what they were doing.’ Aunt Maria was deeply outraged, more so even than for the sake of the raped girls. ‘Field Marshal Boroevic, may you die alone with your nightmares, before the fires of hell strip the flesh from your bones!’ I had never before heard her curse anyone. She usually preferred irony to invective.

Between Enemies

Between Enemies